by Gideon Kwame Sarkodie, HJN Ambassador Ghana

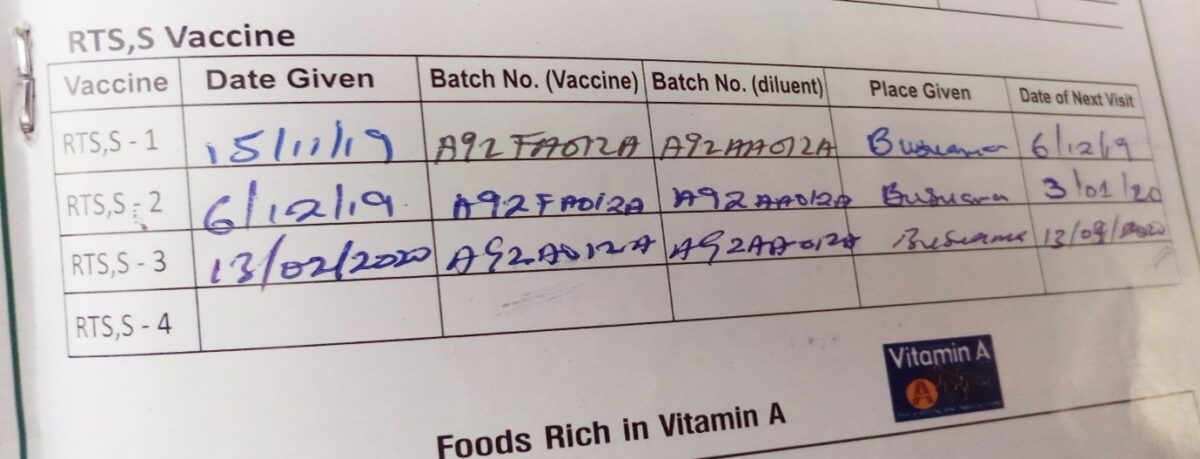

In a small room at the Kadelso Health Centre in the northern part Ghana’s Kintampo North Municipality, eight young mothers are sitting on a wooden bench, each with a 6-month-old baby on their lap. Across from them, behind a desk, sits Janet Adugbire, a Registered Community Health Nurse. A colleague is busy preparing a vaccine, tapping the syringe to dislodge bubbles. Janet explains the procedure to the women, writes down the vaccines’ serial numbers in the children’s vaccination booklets, and copies them onto a spreadsheet in his binder.

Then, one of the mothers bares her son’s thigh for the shot; he starts to cry, and she strokes his back. The procedure is repeated for the other baby, a girl. It may sound routine, but it’s not. These two children have just received the first malaria vaccine to be provided as part of routine immunization—a landmark event in the battle against a disease that each year takes more than 400,000 lives, most of them children in Africa. Thirty years in the making, RTS, S, also known by its brand name, Mosquirix, targets Plasmodium falciparum, the most common and most lethal of four malaria parasite species. It is an answer to a dire need. After decades of declining numbers of cases and deaths, the fight against malaria has stalled. Parasites resistant to the most widely used treatment, called artemisinin-based combination therapy, are spreading, while malaria mosquitoes are increasingly resistant to insecticides.

And yet the pilot rollout, here and in two other African countries, isn’t quite the breakthrough the field has been waiting for. Mosquirix’s efficacy and durability are mediocre: Four doses prevent 4 in 10 cases of malaria and 3 in 10 cases of severe malaria, with protection against severe malaria lasting seven years… The vaccine also has the potential to reduce hospital admissions and blood transfusions that are required to treat life-threatening malaria anemia.

Rather than rolling out the vaccine across Africa, the World Health Organization (WHO) decided to provide the vaccine in selected areasof Malawi, Ghana. By the end of April 2021, more than 650,000 children across the three countries will have received at least one dose of the vaccine.

The pilot is not a clinical trial, but a closely monitored vaccination program to collect more data on the vaccine’s performance in routine use. “I think the pilot is a scientific and pragmatic way to move forward,” says Dr. Kwaku -Poku Asante, Director of the Kintampo Health Research center in Kintampo who has been involved in several clinical studies with the vaccine. “It is a way to monitor all the aspects of the vaccine and watch if something happens.”

Development of the RTS, S malaria vaccine began more than 30 years ago. Large-scale clinical testing of the vaccine between 2009 and 2014, involving thousands of young children in seven African countries, including Ghana, showed that children who received the vaccine suffered fewer episodes of malaria illness, including severe malaria. Clinical studies in Ghana involved more than 2,500 children at two sites—Agogo and Kintampo.

The malaria vaccine has been found to have an acceptable safety profile. In July 2015, the European Medicines Agency, a stringent medicines authority, issued a positive scientific opinion of the vaccine, stating that its benefits in preventing malaria outweigh potential risks. In 2016, WHO recommended phased implementation of the vaccine in selected areas of Africa, following the joint advice of global advisory committees for malaria and immunization.

After responding to a call for expressions of interest from WHO, Ghana was selected as a pilot implementation country in 2017, due in part to its well-functioning national immunization and malaria control programmes. In 2018, the Ghana Food and Drugs Authority approved the vaccine for use in the phased introduction.

Ghana is one of three African countries (alongside Kenya and Malawi) that is carrying out the Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme (MVIP) with support from the World Health Organization (WHO) and in collaboration with partners, including PATH, a non-profit organization, and GSK, the vaccine manufacturer.

There is also close monitoring for any adverse events following immunization. The aim in Ghana is to vaccinate at least 120,000 children per year for three years in the selected areas and to:

- Determine how best to deliver the required four doses of the vaccine in routine settings

- Assess the vaccine’s full potential role in reducing childhood deaths; and

- Establish the vaccine’s safety profile in the context of routine use.

The programme includes areas of Ahafo, Bono, Bono East, Central, Oti, Volta, and Upper East Regions. Within these regions, some districts are receiving the vaccine, while others are expected to receive the vaccine at a later date.

In Ghana, the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) is leading the phased introduction of the malaria vaccine in these targeted parts of the country where malaria transmission is highest. This phased introduction is meant to allow the programme to learn about the impact of the vaccine on preventing severe malaria and deaths in children and about whether parents bring their children on time for all four doses.

At the New Longoro Health Center, Mr. Frank Yeboah, Disease Control Officer says, parents are seeing some reduction in malaria incidents in their children and are beginning to attribute that to the Malaria vaccination,” parents who were initially hesitant to the vaccine have now become ambassadors for the program. Those who had received up to 2 doses are testifying of a reduction in malaria incidents in their children. When they bring the children and we test and show them the results and it is negative, they start smiling and begin to suggest to us that, it is due t the vaccines given to the children.” However, the pilot is still collecting data on the vaccine’s impact on malaria-related illness and child deaths.

At the Busuama Health Center, Registered Community Health Nurse Brenda Takyi – Sarfoaa says patronage of the vaccine is very encouraging, “as for Busuama, I can confidently say that all parents are happy to present their children for the malaria vaccination.’’

The malaria vaccine, much as other health interventions, are not without challenges. The common challenges identified across all implementing Districts are the difficulties in accessing hard to reach areas, especially riverine communities and also intermission in attendance by parents.