Reflections of a reporter on the frontlines of global health

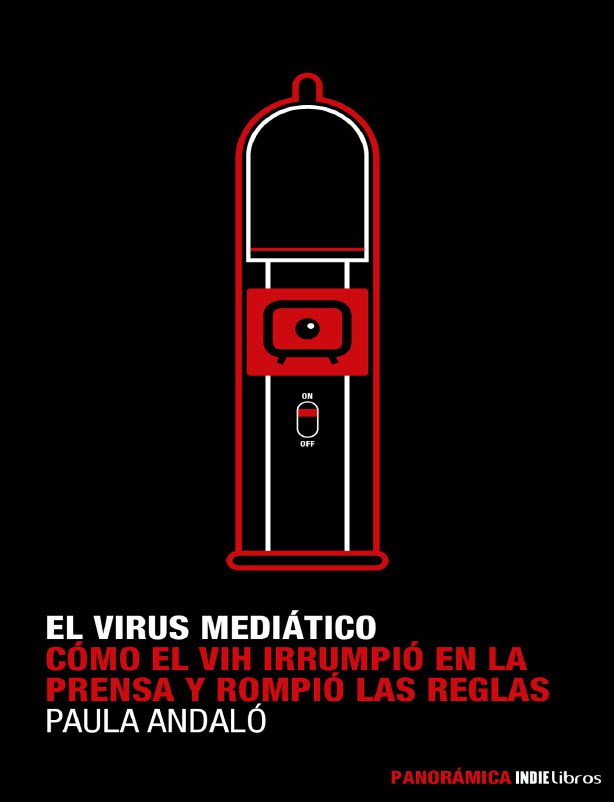

When the HIV virus was ravaging the gay community in San Francisco in the early 80s, Paula Andalo was a young reporter in Argentina who had a health column. This was a time when health was barely considered news and women journalists were often assigned to it. Little did she know, at the time, that health reporting would become her life’s passion and that HIV would be the first, but not the last, global pandemic she would cover. Fast forward 30 years and Paula’s book El Virus Mediático: : Cómo el VIH irrumpió en la prensa y cambió las reglas (The Media Virus: How the HIV Broke into the Press and Changed the Rules) on HIV reporting is launched in early 2020, a timely reminder that some challenges in health reporting are ongoing.

Bea Spadacini, Manager of the Internews Health Journalism Network, had a virtual sit down with Paula Andalo, now the Ethnic Media Editor at Kaiser Health News, to discuss her book on reporting HIV and some of the parallels with covering the COVID-19 pandemic.

In a few words, can you share with us the biggest differences in how the media, in your opinion, is covering COVID-19 versus how it covered HIV in the 80s and why this is so?

Paula Andalo (Paula): Well, the big difference is the internet. When the HIV pandemic began in the 80s, the internet did not exist, so the dissemination of information and the news cycle were completely different. The internet also affects many other things. For example, it affects how information circulates and the sources and voices around a news become different. When comparing the two pandemics, HIV was basically covered by journalists in newspapers and in big TV networks. I cannot say that there was no misinformation because there were many points of views, especially with an infection like HIV that involves sexual, personal behaviors.

However, both with COVID and HIV journalists must deal with many uncertain things. There were uncertainties about a lot of different things. Why? Because the doctors and the scientists didn’t know what was going on. In other words, what was this virus that was killing gay men in San Francisco? And now, what is this virus that is killing people in China and it’s spreading around the world, just as HIV did? So, the big dilemma was and is, how we can transmit information about something we don’t really know much about?

I think with HIV the point was – and is with COVID-19 – keeping the public informed about the developments, let them know that scientists were working hard to have vaccines, therapies, to end the pandemic . Of course, at the beginning of the pandemic, the numbers were an obsession, looking at new cases and new deaths. It was very challenging, both before and now. Dealing with this level of uncertainty puts the reporters in a difficult position. Not only do they have to inform about something new, but they must deal with scientists who also don’t know everything.

What is interesting when comparing coverage in both pandemics, is that at some point the doctors stop being like “Gods.” Before, we reporters and editors were going to the doctors and asking for their opinions when there was a new drug or a treatment, and they were like the Voice of God. At some point in the HIV coverage and all the dynamics of the pandemic, different voices became as important as the doctors. I am referring to patients’ organizations, public institutions, non-profits, and various levels of the departments of health. They didn’t replace the voice of the doctors, but they balanced the power of information.

What about in this pandemic? Is the same happening now?

Paula: Well, I think this happens more than ever in this pandemic, especially with government organizations – at least in the United States and in some European countries – that are fighting against scientists. There are also lots of organizations of COVID-19 patients and even COVID-19 survivors. Why? Because no matter if you are a survivor or a victim, or if you have died because of COVID-19, there is a level of stigma. It happened with HIV patients in the past, and it can still happen now. It can also happen when someone dies of overdose or of suicide or even lung cancer. People say, if you’re a smoker, then it is your fault. If you overdose, it is because you are an addict. With COVID, the same phenomena happen. You must have pre-existing conditions, or you are obese, or you have hypertension, or you are a diabetic.

I never thought so much about the stigma side of COVID-19, but perhaps people want to justify why other people get COVID-19?

Paula: I think it’s all about fear. When we think of the stigma about COVID-19 – at the beginning of the pandemic at least – the victims of stigma were the Asian people. Why? Because this idea that COVID began in China and was created in a laboratory, that was driven by conspiracy theories. In the 80s with HIV, it was about “the gay people” and their “controversial behaviors” that could lead to this kind of infection. So, at the end of the day, the “infected people” are perceived to be responsible.

At Kaiser Health News we ran a very interesting story about families of victims of COVID. In the story, n owner of a funeral home in Georgia mentioned that some people don’t want that COVID appears a a cause of death in the death certificate of their loved ones. They don’t want either the word COVID in the obituary or in the news or any outgoing message. That is the reason why one family that lost a member to COVID-19 who was not vaccinated and was against the vaccine, put the cause of death on the gravestone – showing that he died because of COVID-19. This was a reaction because some family members were implying that he died because he had pre-existing conditions, that he was a smoker at some point in his life, etc. Again, at the end of the day, it is all about fear. So, how do reporters inform the public about this? I believe it is about telling all the sides of the story. There is no panacea when we talk about COVID-19, but we know that there are developments. We know there are vaccines, and the facts tell us that they work. Why I’m saying this? Not because I’m in favor or I’m against vaccines but because I am a journalist and I look at the facts and “I trust,” in quotation marks, the institutions that promote science. I believe in science, even if the verb “believe” is not the proper verb to use because it is not a religion.

But as a journalist, you also hold them accountable, right?

Paula: Yeah, exactly. Looking at the numbers, we can see that these vaccines work. My philosophy is that people have the right to know. It is not my role to protect people. My role is to inform them.

What about the HIV vaccine? Why, in your opinion having covered HIV, there is still no vaccine for HIV and yet there’s so many options for COVID-19? Is it a question of financial resources and/or political will?

Paula: No, I think it’s about the viruses and how different they are. Some are easier to control. We can see that with the flu. The influenza is a virus that we can control using a seasonal vaccine. That could happen with COVID. We don’t know yet, but it could be a seasonal vaccine at some point. I think it’s basically about that. I don’t think it’s about financial resources. There are many clinical trials on HIV vaccines. Pharmaceuticals companies and institutions financed by governments are investigating even the neglected diseases such as river blindness or even Chagas. It is about the challenge of the viruses and how they mutate, and how the variants work. Of course, COVID-19 now is the source of “wealthiness” for a lot of people but that is how it works. I mean, they started to research vaccines when SARS or MERS appeared in at the beginning of this century. Then they stopped because the viruses disappeared, they were restrained or they did not become a pandemic. Hopefully, with COVID-19, we will have resources for a while, not because the pandemic lasts forever, but because we will be able to deal with a virus that is already among us.

Do you see any parallels between HIV and COVID-19 when it comes to health access and treatment for vulnerable populations?

Paula: Definitely, yes. There is a gap in the health system that needs to be addressed before these viruses appear. We can see with COVID-19 how the virus impacted harder on vulnerable populations that have different kind of barriers. I am talking about the Latino population, the language, the access to health care. There are a lot of factors, and we need to address them. With HIV more work had been done because we have had more time. People have been working on it for decades. This is one year. We are talking about 18 months or less. In the United States, there’s a great network of community health centers that can help a lot. During the HIV pandemic, I remember there was an activist in San Francisco, Bobbi Campbell, (he was portrait in the movie “And the Bands Played On” about the beginning of the HIV), Campbell was a nurse and he was one of the first 16 cases reported by the CDC in 1981. He simply made posters and flyers and put them in pharmacies along the Castro neighborhood in San Francisco. These posters said, “Here is this virus. This is what happens. If you have this, this, and that symptom, please go see your doctor.” It is that kind of simple community outreach that is also happening now. You have health workers in community health centers that knock doors in Latino neighborhoods, and they educate people about the vaccine, and they are successful. I think that kind of work is the platform needed to begin to fill the access gap. That and laws that prevent the insurance companies to discriminate people because they have preexisting conditions or because they are old.

When I was reading your book and thinking about the current pandemic, I was thinking about the issue of behavior change. During the HIV pandemic it was very controversial because you had to talk about sex, using condoms and how to protect oneself? Now here we’re dealing with a mask. How do you, as a reporter who has reported on both pandemics, approach behavior-change messaging, or information about it, and how do you see similarities and differences between the two pandemics?

Paula: In both pandemics, there is secrecy if you are infected. Even if the source of infection is different, both pandemics confront people with their own intimacy and behaviors. I think we want to protect ourselves. We have enough consciousness to want to protect our own community. That means we use a condom if we think we are engaging in risky behaviors or have multiple partners. We use a mask because it’s simple. It is a mask. A mom says, “I put my kids’ mask on as I help them put their shoes on.” I mean, it’s a mask. A highly politicalized item now. We can use it when we go to the store when we go to buy food. It is simple behavior change.

Putting on a face mask seems much simpler than convincing people to use a condom!

Paula: Exactly and why? In the condom situation there are two people at least involved and you may have to decide. OK if my partner doesn’t want to use a condom, I don’t want to be with him or her. Or yes, I want to. But with a mask, the same thing could happen. For example, if you go to an in-person school meeting. Some parents say they are vaccinated, but you keep the mask on, while the others do not. Their feelings could be, “these people don’t trust us,” so, it’s challenging, but what we must keep in mind – and what I think reporters can help with, is to demonstrate how this behavior changes things. Why? Because in the community that is fully masked and they are following all the norms, the virus went down. In the community where people don’t use masks because they say that the masks affect their privacy and their human rights, etc… the virus is up. So, you can use that information and report on it.

With HIV, it was harder to tell of course, but you can still notice a difference in areas where there have been recent HIV outbreaks, where there is drug use coupled with needle exchange programs. Infection rates are lower. I think it comes down to government decisions and our own personal behaviors.

When you look at the level of misinformation, disinformation and conspiracy theories and you compare it back to HIV, are you completely overwhelmed by what is going on now? And is this going to get worse with every disease because of the sheer amount of information that we have now?

Paula: The internet is a great resource. People can find things on the Internet that we thought impossible before. That said, social media and not just the internet, can be a huge platform for misinformation. When the HIV pandemic began, I remember someone making an absurd statement that those responsible for the HIV pandemic were Haitian professors who had returned from Africa and disseminated the virus. That was ridiculous! There was no reason to believe that, but one person said it and the absurdity spread. I cannot imagine this same person saying this today and the impact on social media, going exponentially to hundreds of thousands of people.

But at the beginning of HIV, there was also a lot of misunderstanding on how the virus was transmitted right?

Paula: Because unfortunately the first cases where among the gay community, and even when the CDC reported about cases among heterosexuals, the media didn’t pick that information up immediately. So, the myth that HIV only affected gay people lasted for a long time.

So, did the media have responsibility in riding this news cycle? What’s your take?

Paula: Well, it is not just the news cycle but also the way we received information was different. In the 80s we had to wait for the scientific magazines, the physical papers to come to our homes or to the newsrooms. We could talk with doctors or travel to conferences, but we did not have information at our fingertips like we have now. It was different. Of course, if you have information that HIV could spread through heterosexual sex, and you do not say that, then you are responsible. At the same time, you also have the responsibility to talk about people living with HIV instead of talking about “infected people.” You are responsible for how you use language and what you do with the information you have.

What is your perception of media coverage of COVID-19 in Latin America?

Paula: I don’t follow the coverage over there as I follow it in the U.S. of course, but I think the phenomena of misinformation versus good information is global. I know that in Argentina there are many responsible scientific reporters but there are also reporters who can say something silly and then it is out there on the networks. There is always a balance and I think that is part of our responsibility as reporters to strive to be accurate and to balance information.

Do you have any concrete tips for reporters who cover health? You have been a health and science reporter for a long time, how can reporters navigate the uncertainty that comes with evolving science?

Paula: I don’t think reporters have to tell people what to do, but we can give people resources. We need to use different sources. We must doubt. We must ask two or three times. We must not rely on the information that comes from the pharmaceutical companies because there are interests and profit motives. We need to use a variety of sources. One of the most common mistakes among many reporters is that they have their ten sources, and they go to them again and again and again. I say you need to find people from different backgrounds. They are not only scientists whose last name is Smith. There are Latino scientists, and you must put faces on the people in your stories. It is challenging, especially in the middle of a pandemic but talking to people who have the first-hand experience is important. It is easy to collect sources online, but you must do the groundwork. Grassroots reporting is always better because it’s helps you understand and feel things in a different way. Nothing beats the reporter with the small notebook taking notes. If you are not sure, you can transmit that. You don’t lose authority as a reporter if you communicate that you are unsure, because, yes, you are only human.