by Beatrice M. Spadacini

They are periodically targeted for their investigative work on human rights, corruption, migration, and violence against women. They are trolled online, regularly intimidated, and have experienced sexual harassment throughout their careers. But, their passion for exposing abuses and for journalism persists.

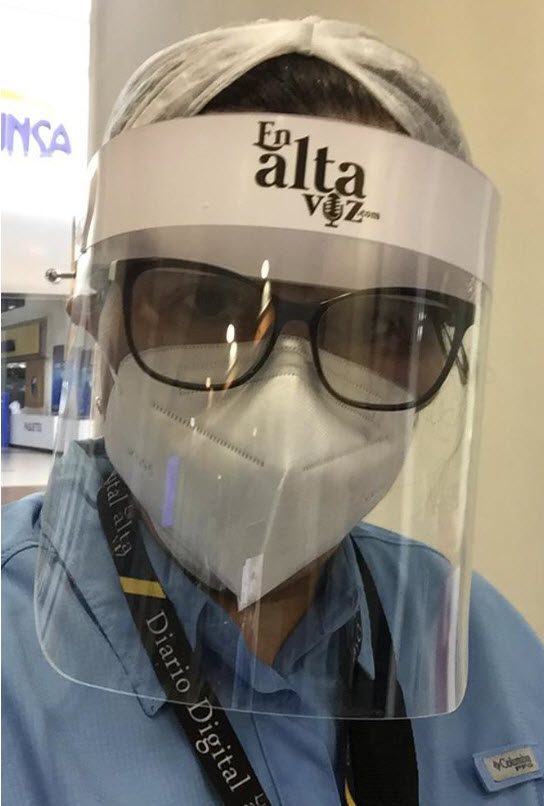

A small group of female journalists, with the support of a photographer and a webmaster, are the engine behind En Alta Voz, an independent digital media platform in Honduras and a member of the Internews Health Journalism Network.

“The pandemic hit us hard,” says Francisca, the founder of this news platform whose name we intentionally changed. “For years, I was able to fund our platform through my consulting gigs, but everything came to a halt with the COVID-19 pandemic. I had no work and if it were not for a bit of funding from Internews, we would not have made it.”

To maintain its editorial independence, En Alta Voz does not accept any advertising money. The outlet relies on donations, grants, and self-funding. Francisca made this decision back in 2017 when the radio program that she and her colleagues hosted was abruptly taken off the air.

The price of editorial independence

“On our show we spoke about many different topics, including corruption, children living in the streets, poverty, and other social topics. It was suddenly closed, from one day to the next. We had a one-year contract but that made no difference,” says Francisca when asked what prompted her to launch En Alta Voz. “That is when we decided we would go digital. We did not want to be censored anymore.”

Their investigations are audacious and bring to the surface issues that are often unreported in mainstream media like labor conditions in contract factories that manufacture for international companies. With over 170,000 factory workers in Honduras, there are plenty of untold stories.

“Once I investigated a case about a pregnant woman who was working in a factory and was not allowed to see the doctor for her prenatal visit when she was feeling unwell. They gave her a pill and a few weeks later she became ill with pre-eclampsia. Now her kidneys are permanently damaged,” says Francisca. “There are many cases of women whose health has been compromised because of their work in the factories. Some of them lose their jobs and live with chronic pain unable to find other jobs.”

During the pandemic, En Alta Voz did several investigations on the dramatic rise in violence against women. The outlet recorded more than 10,000 reports of domestic violence in 2020 alone via the hotlines they monitor and the organizations they work with.

“During the lockdowns, there was a lack of response from the authorities and even the justice department was operating with a reduced workforce,” explains Francisca, adding that only five percent of the reported cases had any follow up.

She says that during the pandemic women had no means of transportation to report cases of abuse, and all social services came to a halt. “Many women were trapped inside with their aggressors and rapists. There are cases of women who were raped by their neighbors and they were stuck. They could not go anywhere as we were under a curfew at different times during the pandemic.”

En Alta Voz also reported on the emotional and psychological toll of the pandemic on women as they had to take care of the children when the schools were closed, the elders and the sick. Many families also did not have the means to afford online schooling. “The emotional and psychological impact on women has been huge and this has to do with gender roles in our society because men don’t have the same responsibilities as women,” says Francisca.

Toxic masculinity and its impact on young female reporters

As a mother of three girls, Francisca is well-aware of the specific challenges that women face in countries where toxic masculinity, or Machismo, is the norm. Being a journalist was a calling for her but throughout her career, especially as a young reporter, she faced periodic sexual harassment in newsrooms and targeted threats as her stories challenged those in power.

“In January of 2020, we presented in a public forum the results of an investigation that we did on violence against women, which started in 2016. There was a man taking pictures at the event and a few days later I was being followed by a car. I then saw two motorcycles parked outside of my house and received threating calls. My family had to move to a safe location, and I had to leave the country.”

When asked if she ever regrets becoming a journalist, Francisca answers without hesitation, “I cannot imagine doing anything else. Today, we need good journalism more than ever.”

This was not the first time that Francisca had to go abroad for a few months to find refuge. After receiving a prestigious award from an international media organization, she was forced to leave the country for a few months to keep herself safe.

In Honduras there is a committee to protect journalists and human rights defenders but, according to Francisca, they don’t do much apart from filing official reports, which in some cases only make matters worse. “What is needed is an organization that offers journalists protection when our lives are threatened. It is important that those who intimidate us know that we are part of this network, that we are protected. I do not want to leave the country. I want to stay here and fight for my country.”