by Kathryn Cleary

“We’re trying to break the cycle, or reverse the tide,” says a passionate Aynabat Yaylymova founder of Saglyk, a website dedicated to improving public health literacy in Turkmenistan. Originally from Turkmenistan, Yaylymova, a member of the Internews Health Journalism Network, is well-aware of the information challenges faced by people in her home country.

On top of limited access to the internet, she says that the available public health information has a small reach, and mostly consists of brochures from the Ministry of Health and international organisations like the United Nations and the U.S. Agency for International Development. These brochures seldom reach the larger population, says Yaylymova, and the content developed by international organisations is not published online, nor is it available in Turkmen.

To address this information gap, Saglyk launched just over 10 years ago in 2010, and has become one of the only online sources of accurate and unbiased health information available in Turkmen. “If you cannot name something, you cannot address it,” says Yaylymova. “Our readers say ‘thank you so much’, we have no other place to read about medical news, to read about what’s happening with research in science and medicine,” says Yaylymova.

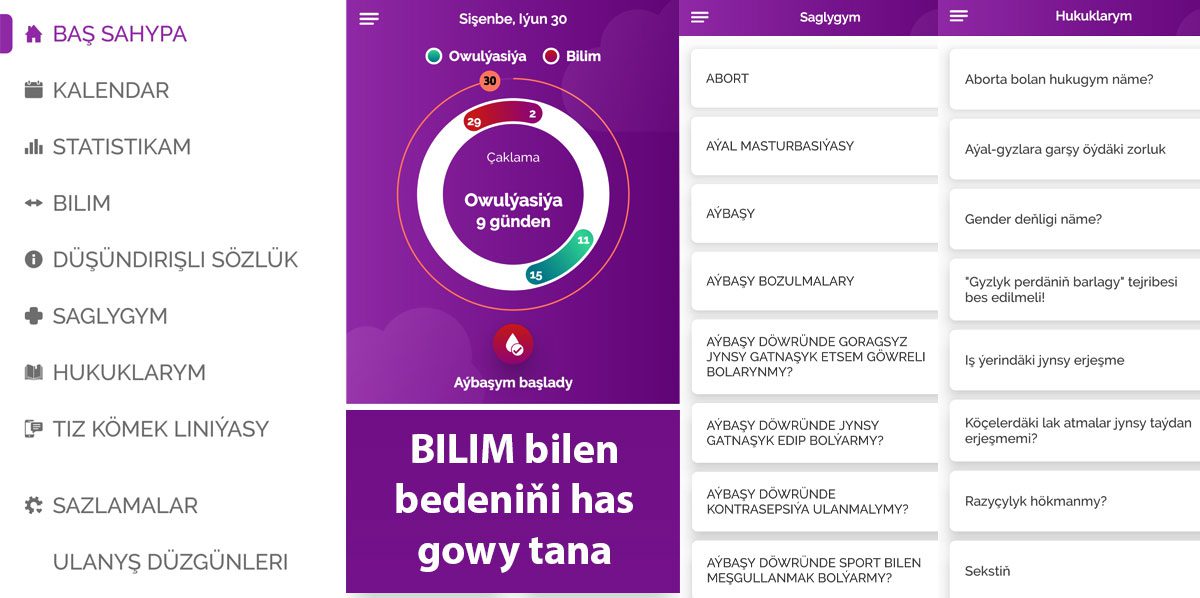

Last year, Saglyk launched a mobile app called Bilim, which is packed with information for women and adolescent girls about the menstrual cycle, their sexual and reproductive health and rights. In Turkmenistan, this is a necessary resource that addresses historical health information gaps.

We have 42 articles on the app, and we keep adding articles on reproductive and sexual health, and, so far, it’s positive. We’re also developing an e-book right now for teenagers with 100 questions they cannot ask their parents. It’s questions about relationships and anatomy, biology, pregnancy, everything. We’ve reached a point, where we are very proud of our content and we can use it, and recycle it, and change it.

“[Turkmenistan is] conservative and patriarchal, and it’s gotten worse over the 30 years since the break-up of the Soviet Union. It got worse, the traditionalism, nationalism, all the types of ‘isms’,” says Yaylymova. “On the background of human rights, it hits the more vulnerable populations [the worst]: children’s health and rights, women’s health rights, for me it’s very important to talk about child mortality, or maternal mortality.”

While Saglyk has about 2,000 published articles online, Yaylymova says that they do not have permission to compile and print these articles into books within the country. “Only about 300 books get published in Turkmenistan in Turkmen every year, so you can imagine there are no science publications, nothing on epidemiology. The denial and misunderstanding of science, as well as increased use of traditional medicine is a very, very dangerous situation for the society,” she emphasizes.

Yaylymova comments that in Turkmenistan’s own “development puzzle,” the issue of internet access as well as access to outside information is a key problem. She says that young professionals who were born roughly at the same time as the country gained its freedom from the Soviet Union, often visit neighboring countries for work, trade or what she calls “mental breaks.” “They see how the world lives, and then they come back and use their phones or they try to get information and they’re frustrated. We should not wait with content development until Turkmenistan realizes how shutting down the internet makes the whole society backwards,” she emphasizes.

As a project, Yaylymova says they would like to work with the Turkmenistan government to collaborate on making public health information more accessible to the public. “We know that in neighboring countries like Kazakhstan or Uzbekistan, the government welcomes those kinds of projects to a certain degree.”

We are very open about our offer to engage and cooperate with the Ministry of Health, but so far we’ve been treated with silence.

If we were to follow a traditional Soviet mentality, as Yaylymovacalls it, “this gigantomania mentality” where every project must be big, we would not have the same impact, she says.

“The small projects make a big difference, small projects that really matter for an average person. It’s not criticising the government, but it’s basic information [about] COVID-19, how not to spread it, those types of [things.]” Regardless of internet challenges and Saglyk’s small size, Yaylymova urges others to not be hesitant to test and see the value and impact that these small projects can have.

Breaking the cycle of poor access to public health information and reversing the tide of the “taboo” in Turkmenistan is Saglyk and the Bilim App’s mission. This organization is making a big difference under less than perfect circumstances.